With increasing collabs between artists such as J Balvin and Mr Eazi, MC Galaxy and Nacho, or Maluma with Maître Gimz, not to mention that 2019 Superbowl half-time show where Shakira ‘paid tribute’ to Africa with her dance moves, West African and Latin Music is definitely having its moment. There may be commercial reasons for these collabs, but there is also an undeniably eazy flow between these African and Latin artists that might surprise people. So, what is it that is bringing these pairs together? And why does it work so well?

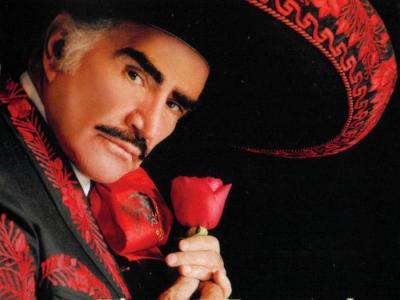

“All music comes from Africa. There is a different rhythm and melody in each specific area, but every Latin rhythm can be traced back to Africa. They share the same DNA,” says DJ Jose Luis, pioneer of the UK reggaeton movement with his legendary La Bomba parties at Ministry of Sound. “Take the original version of the dembow rhythm (the backbone of reggaetón) and it was a dancehall called the Poco Man Riddim by Steelie and Cleevie, first recorded in the 1990s in Jamaica. Reggaetón is an an evolution of dancehall, African-rooted, and in a way is a form of afrobeat, you could say a variation or spin-off.”

Indeed, everything that is, has been before: the traditional music structures of Dominican dembow, were played by African slaves in the 1800s, in order to communicate with each other because they all spoke different languages. Puerto Rico, where reggaetón is most associated with, is also the home of bomba and plena – genres of music and dance rooted in the island’s history of African slavery. Panama, arguably the true home of reggaetón, had its own original slave population. Then another layer of immigrant workers came from Jamaica in the 20th century to build the Panama Canal, making an even richer musical layer-cake that fused Latin music and reggae to become the earliest expression of reggaetón in the 1980s.

African rhythms permeate Latin music everywhere, from Colombia and Venezuela to Central America and the Latin Caribbean. So when, in 2019, audiences were wowed by what they thought was Shakira’s “tribute to Africa” with her dance moves at her legendary Superbowl half-time show, “she wasn’t paying any tribute to Africa, I don’t think,” Jose Luis argues, “she was dancing ‘champeta’, a style of music and dance originating from Cartagena de Indias, where she is from.”

This perfectly encapsulates the mixing of reggaetón, or area-specific Spanish music, and afro-beat, and how its historic links translate into everything from dance to fashion to music. With new legislation and censuses, the afro-descendent population of South America has been recognised more and more, with Brazil being second only to Nigeria in terms of its population percentage of afro-descendants.

This being the case, is it surprising that any of these African-Latin collaborations are popular right now? In fact, if you look into it, it’s far from new. Anyone who is into their salsa will be familiar with the amazing Fania All Stars concert in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire) back in the 1970s. The historic ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, where Muhammad Ali took down George Foreman in a famous boxing match, had a star-studded line-up like no other. In amongst names such as James Brown and B.B. King, were Celia Cruz, Hector Lavoe and Johnny Pacheco doing their stuff to an intrigued Congolese audience.

“There has always been this cultural back-and-forth,” says Jose Luis. He uses the example of Cuba, which was exporting its own African-infused music back to Africa all through the 20th century, especially Senegal. This influence then saw the birth of fusion groups such as Etoile De Dakar and Laba Sosseh or Africando. Infact, the original Buena Vista Social Club album was supposed to be a recording of Mali and Cuban musicians. The Mali musicians never turned up, and what was recorded instead was The Buena Vista Social Club which became a worldwide hit.

Through touring and collaborations, the Africa and Cuba increasingly influenced each other and formed huge followings in both continents. This flow was not just musical, with many Cuban troops being deployed in Africa under Castro’s regime to support the African decolonisation movements. Many Cubans formed families in Africa and created bases and the musical fusion flourished.

Politics is still very much involved in Afro-Cuban music, argues Jose Luis, citing Cimafunk who fuses pop-afrobeat fusion as Cuba’s most successful Afro-Funk act. “But there is another genre called “Reparto”, which is basically a bastardised dembow beat,” Jose adds. “that is the real music of Cuban youth, typically from less wealthy backgrounds and it is not getting the radio play that CimaFunk is getting. Why? because their lyrics depict their social reality which isn’t always flattering for the government. But reparto is pure Africa, rhythmically more complex than reggaeton. An artist championing this underground Cuban Reparto is Chocolate MC.”

In the rise of afro-beat and reggaeton, politics is never far away. While early 20th Century West African artists, such as the Cape Coast Sugar Babies, initially performed the genre “highlife” for African aristocracy in the 1920s, Fela Kuti started to change the sound in the 1960s using traditional instruments such as the Gbedu drum, together with messages of social justice in response to the military and political corruption at the time.

Meanwhile, across the pond in Panama, thousands of West Indian immigrants were brought to work on the Panama Canal. A few decades later a distinct dancehall-derived sound exploded with names such as El General and Renato igniting the genre. The sound soon spread across the Latin Caribbean, finding an underground home in Puerto Rico that captured the attention of the island’s disenfranchised youth. The initial response to its popularity was governmental crackdown on the genre; raiding record stores, confiscating mixtapes and hefty fines up to $500 for listeners. That was before it became clear that the genre was going to make a lot of money for the music industry, who placed ‘whiter’ faces like Daddy Yankee at the forefront, rendering it more palatable.

Both afro-beat and reggaetón started under the mire of oppression, protest and political subversion. Their similarities in terms of the structure, message and history start to shine through and were nourished through touring, collabs and exports. It seems no coincidence that whether in Africa, the Latin Caribbean or the UK, black music that truly represents its people, has always been met with extreme political scrutiny and violence. It also seems no coincidence that the faces of these genres have often become whiter with industry investment, such as lighter skinned reggaetón stars singing on top of Afro-beat rhythm.

Looking at the larger history of reggaetón and afro-beats and their structural similarity, it comes as no surprise that these collaborations would inevitably become globally chart-topping. By placing the superstars of the genre together with their familiar sounding rhythms, commercial success is a given.

But behind the commercial manouvres of twinning artists, at a grassroots level, the cultural and creative interaction between the two continents continues to grow and thrive organically. “What’s interesting is that now you can hear la clave (the basis rhythm at the heart of all afro-Latin music) in afro-beat, which African artists have reclaimed as their own. It’s like things are coming full circle.”

As streaming services have increased and the internet has levelled the playing field, allowing more and more artists to upload content, more local voices are being heard. If we have learnt anything, it will be that these transformations cannot be stopped and can even reach the public without manipulations and interests of ‘the industry.’ But the most important thing is to appreciate the roots of these changes and the long history of pioneers behind them.