Hip-hop has two enduring characteristics – self-made music with few resources, and a reflection of marginalized communities, the discrimination and challenges they face. As the movements develop, they often split between the people who maintain loyalty to their roots and to social activism, and those who see commercial success coming their way.

Portuguese rap and hip-hop are not well known, the only thing that comes up in a search for Portuguese hip-hop is Latinolife's own Batida Lisboa, a film about musicians in an African migrant area of Lisbon on the north bank of the Tagus in Lisbon and most of the music mentioned is based on electronic beats that evolved into a mix of Angolan Kuduro House music and techno.

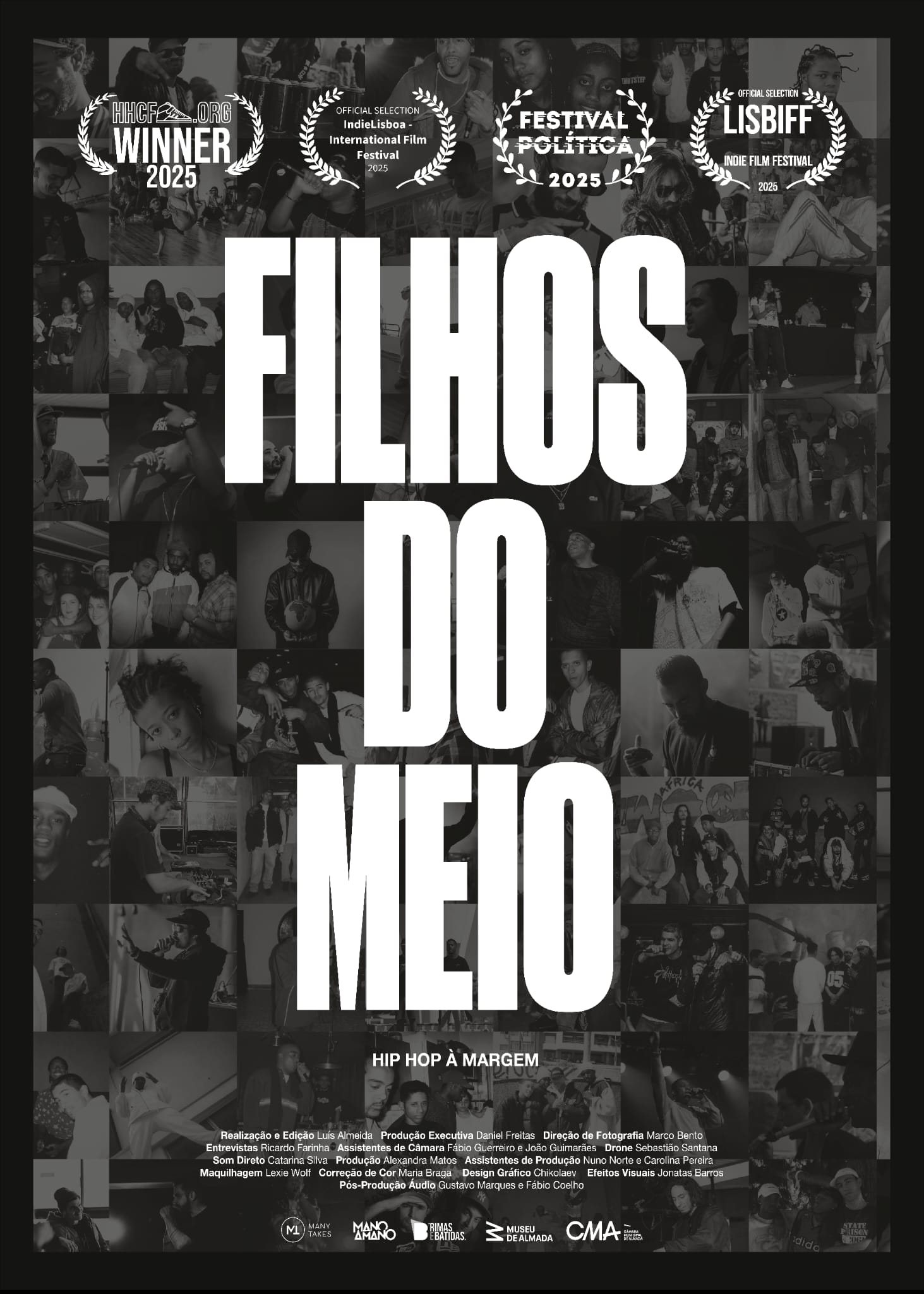

A new film, Filhos do Meio, directed by Luís Almeida, explores a movement which emerged out of Lisbon's Margem Sul (South Bank) over 40 years, including Almada and Miratejo, in the early 80s, where Cape-Verdean culture is very strong. Early influential US groups included Public Enemy whose political interventionist lyrics impressed General D, born in Mozambique but who grew up in the Margem Sul.

The first album to really put Portuguese Hip-hop on the map, Rapública didn’t arrive until 1994. As the movement developed the use of English – from US hip-hop influence shifted to Portuguese, and to Cape-Verdean Creole. But influences have been diverse; Mind da Gap, a group of white guys from Porto, is more poetic than political, are influenced by rock, the influence of London is clear here, while Da Weasel, began in a thrash metal and funk environment.

Luís started as a video editor in television and made a small documentary series that revolved around hip-hop as well, called Sol a Sol, from sun to sun, following somebody for one day, who lived this culture. Now Luís runs a production company, when he was invited to make the documentary by Daniel Freitas, Executive Producer of the film, and the film is part of a project that included a 6-month exhibition at the Almada City Council Museum.

“My way of looking at hip-hop, as someone who never lived in Almada, but loves this culture is trying to add to it in the way that I know: making films and writing stories," Luis says. "This movie is just a little piece of a puzzle that is the culture: a little bit of a microcosm around the metropolitan area of Lisbon”.

How would you give an overview of the history of hip-hop in Almada?

The old school, when people were trying to figure it all out, in the mid-‘80s to early ‘90s when people were listening to American and French hip-hop. Everything started with breakdancing, and it evolved to some rapping and some producing. And then in ’94 when Rapública was released, the first hip-hop album in Portugal, a compilation of various artists everything changed.

Phase two begins here, when some rappers started having a career in music, and hip-hop started to be a real thing for the general public. And then you have a mainstream and an underground coexisting. Our film focuses on the underground part because that was less documented. Around ’96 - ‘98, the shift into the mixtape era happened where a lot of DJs were gathering rappers from around all parts of Lisbon and the Margem Sul and the underground gains a lot of traction. In the 2000s this underground movement starts making waves and really creating the foundation to what it is today, a lot of the artists from that era are still seen as icons and important figures.

In 2001 - 2003, underground artists started to release their own albums. Xullaji in the documentary talks about it, Valete and Sam The Kid, albums were a big shift in mentality and how to approach hip-hop. They were very influential in creating a new crop of artists who understood that it's possible to be underground and still release music and start to make a career. M.A.C., Styx, and a lot of other rappers started to work more professionally and developing technology: computers are better, equipment is cheaper. The underground movement is still very much alive. Smaller artists can make a career and do small shows. That's what you see in the later part of the film when we talk about artists like the group ORTEUM, Mura, and people like Catalão, João Pestana, and the new wave of underground rap in Almada. The issues that hip-hop talks about have shifted from social problems to personal ones, like mental health, and living on the edge. The third Phase starts around the 2010’s when hip hop is so mainstream that you start seeing rappers on main stages of the biggest festivals here in Portugal. I think we are still in that phase, where there are a lot of artists with impressive careers and doing very big shows.

There was a point in the film where they were saying, “we kept ourselves to ourselves, what was happening here was really original”.

There was a local movement, but they were listening to what was happening in Lisbon and vice versa. The movement was connected and there was some rivalry across the river. In the mixtapes era, everybody was partying together. Mirasquad was a crew that kept themselves in that neighbourhood because they lived there.

Was input from abroad important in the way things developed?

Definitely. And it goes a bit further because it began with lot of immigrant people, the Cape Verdean communities are present all over the world.

That's how a lot of hip-hop came to reach Portugal and the Margem Sul. Maybe a cousin brought some music from the Netherlands or the United States or Paris, where Hip-Hop was more developed. The diasporas are very important in the way the culture evolved. A lot of rappers emigrated from Portugal, and some came back.

Was Cape Verdean the biggest influence, what about Guinea-Bissau, Angola and the other Portuguese-speaking countries?

The other Portuguese-speaking countries had their influence too, but Cape Verdeans have a really big influence because they can bring things from their diaspora all around the world. Nelson Neves is an example of this, he had family in Paris, so he was one of the first guys to bring hip hop to Almada and is seen as the guy that started de culture there. In Margem Sul, there's a big Cape Verdean community and they are very united. So, things would normally brew in those areas. We are a very musical country, so we are always creating music.

The impression I had was that the lyrics are in Portuguese, not in Creole. Was that deliberate so the music gets a wider audience?

There's a lot of hip-hop Creole in the Margem Sul as well. Juana na Rap is an example of that, she's a white Portuguese woman, but the influence of the neighbourhood made her sing in Creole because it's almost her first language. Nowadays it's even more common, the first generation were still finding out to use Creole in the music, but then it evolved. And now people are singing more in Creole than in Portuguese.

Is there any Brazilian influence in the music that you're producing?

Brazil is a very influential place for Portuguese music. We receive a lot of their music. Probably in the beginning, a lot of rappers started thinking about writing in Portuguese after the first, Gabriel o Pensador album came to Portugal. It was very important for the movement.

It was a groundbreaking album for hip hop in Portugal, and groups like Racionais were very important, so that we could keep writing about our social problems. Brazilian rap is still very big here in Portugal. And even the more The Trap vibe is very big here.

Someone said that hip hop is an important social bonding force for all ages, all generations, especially as a resistance to racism - whether it's skinheads or the system that doesn't treat people fairly.

As someone that grew up on the outskirts of Lisbon, and son of a cleaning lady and a man that worked on construction, hip-hop was the way I could find some social knowledge and understanding of the system. It was the first thing that gave me some political education. It's a tool to know your surroundings and know that we are capable of changing things if we wanted to. Xullaji says in the film that hip-hop was always a collective culture.

Hip-hop is about creating a connection through music, but also hip hop was born out of struggle.

In the Bronx, they were living the same problems that people from Miratejo were living. That's how we connect, that's why it's a global movement, and why it's still thriving today, in a very different way.

Hip hop is beautiful because this community connection helps to understand people in a very deep way. It uses a lot of words, more than most genres, so you can spread ideas and connect with people on a whole other level.

I heard that African history is not taught properly in Portuguese schools.

There are mentions of the African liberation movements, but they don't explain that the revolution started in Africa because a whole lot of ideas were spreading there and not because some soldiers were just tired of the regime: no, they were tired of fighting a war for something that was not worth it.

Our school system still keeps this image of Portugal as a good coloniser, compared to the English or the Belgians.

My grandfather who's 92, had to leave Cape Verde to go to São Tomé to be a worker as they were called. He came back a little older and with no money, but they made a lot of money for somebody, it’s documented.

Portuguese people are still struggling to come to terms with what happened during that period., but we have a lot of amazing, young black activists who are trying to change the view of that period.

Is there any conflict with the collective culture when people start to get more business minded wanting a career?

It's the neoliberal system, you have to make money to survive, it's all about individual success and not about the collective. It's evolution, some things improve, others don’t. But people are making careers out of hip hop. In the nineties, nobody thought that would be possible. So that's good.

Skateboarding was mentioned as being quite important, especially for schoolkids.

In the nineties, people lived a lot more outdoors, so skateboarding was another way to connect. Some people dance, some people play football or basketball. Skateboarding was important in the film because of the group M.A.C.

The film is called Filhos do Meio, Sons of the Environment, but it's a play on words because Meio, means both ‘environment’ and ‘middle’ in Portuguese. It refers to the environment where this movement started, but they are also the middle child of the movement. M.A.C. are the thread running through the movie. That's why they appear at the beginning, and then in the middle, talking about skateboarding and how they were influenced by the guys before and are influencing the guys in front.

M.A.C was made up of TNT, Daniel Freitas who’s an executive producer on the film. He was the one that invited me to do this documentary for him. And Kulpado, who's his best friend since the nineties, they spent a lot of time skateboarding in Almada. That's where they started thinking about music and listening to hip hop, because people would gather there with their headphones, sharing cassette tapes and CDs, while learning new skateboarding tricks. And that's also how they started to learn about the culture.

Some popular films were mentioned as having an influence, The Godfather, and Shaka Zulu.

There were a lot more that were influential that I couldn't fit in the movie.

For the Break Boy, the B-Boys the birth of that whole thing was Beat Street. It influenced everybody starting to break dance. The Godfather was just something that kids watch and get influenced by.

It started a super group in Margem Sul, called Mafia Suliana (Margem Sul Mafia) gathered all the rappers from the neighbourhoods. It was a super group of people that just gathered and was like Wu-Tang Clan. They just spent time together and improvised and went to concerts together. We're a really big group of people that like to be with each other from all neighbourhoods of the Margem Sul. They started because one of the Nexo members watched The Godfather, and said, “this is interesting, let's make a group like this mafia structure”.

They were divided exactly like a mafia, there was a Don and then a Capo, and they changed their names to something to sound a little Italian. Everybody wanted to be connected to Mafia Suliana, because it represented being from Margem Sul and being a real legit MC and not just a sucker as they called them. There was this big difference between commercial rappers and underground rappers, at the beginning of the 2000s and the end of the ‘90s. Being in the Mafia Suliana was a badge of honour.

Shaka Zulu was a big influence on Nelson Neves, the kid who went to France and started to gather information about the hip hop movement. He brought music, he brought the style, and he stood out at school, from the other kids in the ‘80s who were listening to disco. I think Shaka Zulu also influenced Afrika Bambaataa and Zulu Nation and American Bronx were happening in Paris

Juana na Rap and Shiva talked about what it's like, being in the world of rap and hip hop as a woman.

It was very important for the documentary to give them space and voice. There are no voiceovers, they're the ones doing the explanations. Shiva is talking from a position of someone starting in the ‘90s, part of a crew full of men, Nexo, who were very welcoming. They allowed women to participate in the music. She was a rapper herself and was friends with other girl rappers. But the reality in the ‘90s and early 2000s, was that a girl doing this type of music was usually viewed as inferior.

And even if they were good - you saw a great example, JJ, those two girls that are rapping in a train, they were part of a group called D Jamal, that were the first female group to release an album in Portugal in ‘97. They were four girls, and you can see their skills, but they couldn't make a career out of it. Shiva was a young mother with a child and a husband to take care of. For men it's easier because if you have to go out and spend a day in the studio, somebody will take care of your responsibilities.