Almost 20 years ago, in 2006, when we first launched LatinoLife - the UK's first Latin culture magazine - we published an article by DJ Jose Luis, about the history of reggaetón. In it we referenced a landmark moment when, on November 10th, 2004, at Madison Square Garden, a sold out “Megatón” Festival was heaving with the proud and irreverent faces of 40,000 young Nuyoricans, Dominicans, and African-Americans. America’s most important venue was stage to the biggest ever concert to date, of a rhythm invented by a new generation in the heart of the Caribbean.

Here in the UK, DJ Jose Luis had just launched the UK's first reggaetón party, La Bomba, in London's Ministry Of Sound in 2005, which he went on to run for 15 years, under the radar of a UK music media and music industry that ignored the genre. How things have changed! In June 2026, Bad Bunny will be the first Latin artist ever to headline a stadium in the UK, with not one but two sell out shows at Tottenham and Pitbull will become the first Latin artist to headline London's Hyde Park show. The UK media is suddenly all over this Latin genre it dismissed for so long, although still quite unsure what to make of it.

From those shadows two decades ago, inhabited by Latino youth, whether in London, New York or San Juan, a cultural revolution was born. What began as a mix of reggae, dancehall, and hip-hop in the barrios of Panama and Puerto Rico became one of the most influential musical movements of the 21st century — and one of the most misunderstood.

This is not just the story of a rhythm. It’s the story of migration, class, and identity. It’s about how Black and working-class youth across Latin America used sound to carve out space in a world that tried to silence them — and how, decades later, that same sound conquered the global stage.

The Roots: Rhythm as Resistance

In the late 1980s, Panama — a small country shaped by canal-zone segregation and constant migration from Jamaica, Trinidad, and Colombia — became a melting pot of Caribbean sound. Jamaican workers who had come in the early 20th century to build the canal brought with them ska, rocksteady, and dancehall. Their children began translating those rhythms into Spanish, giving birth to reggae en español.

Artists like El General, Nando Boom, and Chicho Man became pioneers, singing over riddims imported from Kingston but giving them new swagger. Their lyrics celebrated barrio life and reflected their social consciousness while making people dance — a mixture of pride and protest wrapped in bass.

Meanwhile, across the water in Puerto Rico, another revolution was brewing. The island’s youth, heavily influenced by US hip-hop, was experimenting with bilingual rap, break-dancing and mixtape culture. The result was a rebellious scene that blended boom-bap beats with Jamaican dembow.

In 1993 San Juan, Puerto Rico, a club called The Noise was the place for young Puerto Ricans to go and freestyle and rap over hiphop and dancehall-ragga tracks. DJ Negro, the resident DJ of the club, released "The Noise Vol. 1" in 1994. The sound was raw, with fast beats and heavy bass. A couple of years later, DJ Negro hooked up with a Panamanian DJ called Chombo and they released Los Cuentos de la Cripta.

Mainstream record labels were not interested in this new material coming out of Puerto Rico and Panama and radio stations boycotted the albums, criticizing their lyrics for being violent and vulgar. After the unlikely success of The Noise series (they kept releasing albums, 10 so far), a Puerto Rican entrepreneur, Raphy Piña, decided to try his luck with the new music and funded Piña Records. He signed almost every MC-DJ-Producer in the scene. Vico C, Big boy, Baby Rasta, Gringo and Don Chezina, to name just a few, had their videos shown in TV stations and their music played in some radios, thanks to Piña.

The content was unapologetically raw. Lyrics spoke about poverty, police brutality and sexuality with a directness rarely heard in Spanish-language music. The government responded with moral panic: raids, arrests, and media campaigns against this “obscenity.”

DJ Nelson’s Xtassy Reggaetón mixtape (including a massively popular version of the Eurythmics’ Sweet Dreams) sold 100,000 copies in 2001. So the police then moved in to stop this mixtape industry, a campaign led by Senator Velda González. Radio executives and a united reggaetón movement took the Puerto Rican government to the Supreme Court. The Reggaetoneros won the case on the grounds of freedom of expression, on an agreement that lyricists would water down their lyrics.

In the end, this gave publicity to the genre and censorship only made the movement stronger. Reggaetón was becoming the voice of a generation raised between colonised identity and global aspiration.

The Explosion: From San Juan to the World

By the turn of the millennium, Puerto Rico’s underground scene was boiling over. In 2000 an MC with a unique flow, husky voice and hard hitting lyrics started getting noticed. Tego Calderon was his name. A black man from the ghetto of Carolina in San Juan, Tego released his first album El Abayarde in 2002. Tego's socially conscious lyrics, deep voice and Afro-Boricua pride connected reggaetón to the country's black roots, challenging the racial hierarchies of Latin pop. Heavily criticized by media and music critics, the album nevertheless blew away those who heard it and sold 250,000 on the tiny island with no promotion.

At the time, many artists got their mixtapes funded by the bichotes, who also financed huge street parties. Artists and DJs a-like have fond memories of this era; the sound and the scene was fresh, the power was still in the hands of the market, the music was close to its source and the authenticity rang through. More importantly the artists were making money from their music, even if the drugs barons like El Boster (aka Angelo Millones) were making a lot more.

“I remember that time with a lot of happiness, it seems like yesterday actually,” says Tego Calderón, now considered the godfather of Puerto Rican reggaetón. “My fans, my public, gave me a lifeline. My life wouldn’t have been easy without music and what its given me so I feel very grateful.

The “clean up” was inevitable, however. The Puerto Rican elite weren’t about to let all the money stay underground. The Puerto Rican/US authorities made an example out of one of the biggest artists at the time, Tempo, by charging and sentencing him for drugs trafficking. With the new interests involved, many of these original artists, like Mexicano 777, were never able to make it commercially because they were tainted by Reggaetón’s street image.

Despite being ignored by the big labels and Latin music bosses in Miami, Tego was soon being invited by 50 Cent to record the remix of P.I.M.P and with Cypress Hill he recorded Latin Thugs. In 2003 he opened concerts for Sean Paul and his tunes were in Tony Touch’s legendary mixtapes. In the autumn of 2004, the multi-million selling N.O.R.E (from Nore and Capone) decided to go back to his roots. He started listening to reggaetón in New York's Latin clubs and released Oye mi canto, featuring Nina Sky and Tego. The single burned the American charts and became the first crossover reggaetón hit, opening the door for the others to come. At the same time, Tego was also recording the remix of the now world hit Lean back by Fat Joe. He also did a cameo appearance in the video.

Meanwhile Multinationals’ Latin music A&R men, were busy nurturing clean cut white Latinos like Ricky Martin and Chayanne. They didn’t like the way the likes Vico C or Tego looked, what they said, how they sounded. And they weren't about to change. “I ain’t trying to be employee,” Tego said. “I have worked too hard to build what I have, I have never been a good employee, I don’t like anyone telling me what to do. Yup, I lose millions…but I keep my freedom.”

But by the mid-noughties, reggaetón was the hottest rhythm in the streets of New York and Miami. Those who thought it would fade out would be proved wrong.

The Respectable Face of Reggaeton Arrives

Just when music bosses had to accept reggaetón wasn't going away, a respectable (dare we say whiter) face arrives with a hit called Gasolina (2004). Everything changes. When Daddy Yankee’s anthem hit global airwaves, reggaetón leapt from the barrios into the Billboard charts. It was the first time a Spanish-language urban track dominated English-speaking radio — and the first time mainstream audiences danced to the dembow without even knowing its name.

While Tego was turning down sponsorship deals, Daddy Yankee was willing to take up all the commercial offers thrown at him. He accepted the offer from Puff Daddy to promote his clothing line that Tego refused (because of Central American sweatshop links) and the Pepsi deal. When Gasolina was remixed by Lil’ John, it became an instant hit in the US R&B charts and took Daddy Yankee and Reggaetón global in 2004, from BBC Top of the Pops appearances in the UK to Iraq, where the tune resonated with a generation invaded for its oil. Weirdly, Gasolina became the anthem of Iraqi boys selling petrol on the black market at street crossings.

Record labels saw opportunity. The early 2000s were a transitional moment for the industry: Napster had shaken up CD sales, MTV was chasing the next youth movement, and the U.S. Latino population was booming. Reggaeton, with its bilingual swagger and irresistible beat, was perfect.

Major labels created new divisions like Machete Music (under Universal) to commercialise the phenomenon. Collaborations with hip-hop stars followed, Wisin & Yandel’s duets, Don Omar’s cinematic albums — and suddenly, the sound of the Caribbean was everywhere.

But success brought contradictions. What started as anti-establishment expression became a pop commodity. Reggaetón was no longer dangerous; it was marketable. Its Afro-Latin identity was often softened for crossover appeal, and radio demanded cleaner lyrics. The underground rebel had become a global star — and some feared it had lost its soul.

The Industry’s Dilemma: Profit or Pride

During its commercial peak (2004-2008), reggaetón lived a paradox. On one hand, it gave visibility to Latin urban culture like never before. On the other, it faced accusations of monotony, hyper-sexualisation, and machismo. Critics argued that the genre’s original social commentary had been drowned out by formulas designed for nightclubs and product placement.

Inside the industry, power struggles erupted. Many pioneers were sidelined in favour of newer, more photogenic artists. Record executives — most of them from outside the Caribbean — sought to control what they barely understood. Reggaetón became "Urban Latin" - easier to market that way.

Meanwhile, new talents who have made it big through years of hard work, good management and talent like Don Omar and Wisin & Yandel, created their own labels and snapped up new artists before the major US labels latch on, while A&R men of big labels continued trying to catch the trend. This has meant that, even though there is less money in it, the artists themselves are reclaiming control of their music in the same way to when it all began, promoting their own music via the internet.

Artists such as Pitbull, the Miami-based Cuban-American became household names, Panamanian singer, DJ Flex became an eight times Latin Grammy Award winner in 2008 and Calle 13 became the urban latin artist to win most Grammies ever, even with his political poetry. Ivy Queen broke gender barriers and even Shakira began cashing in on the genre. Their voices reminded audiences that reggaeton was more than a party — it was a mirror of society.

But as radio saturation hit, public fatigue set in. Around 2009, the genre’s global momentum slowed. Pop and electro took over. Many declared reggaeton “dead.” They were wrong — it was only hibernating, waiting for a new generation to reboot it.

The Rebirth: Urban Latin and the Digital Revolution

In the 2010s, the music world changed again. Streaming replaced CDs. YouTube replaced MTV. For young artists, that meant independence. No more waiting for labels or radio — just beats, Wi-Fi, and hustle.

This is where Colombia enters the story. Cities like Medellín became new creative hubs, with studios producing hits that fused reggaeton’s rhythm with pop, trap, and R&B. Artists such as J Balvin, Maluma, and Karol G introduced a smoother, melodic sound — less raw than the Puerto Rican underground, but more global in reach.

At the same time, Bad Bunny emerged as the bridge between worlds: fiercely Puerto Rican, proudly weird, politically vocal, yet commercially unstoppable. He brought back the genre’s rebellious energy while expanding its aesthetics — wearing skirts, defending workers’ rights, and rapping about identity and grief.

Urban Latin became a broader umbrella that included reggaetón, Latin trap, and all their hybrid children. Some saw it as evolution; others as erasure. Industry executives could sell the music without confronting its racial and social baggage, but artists themselves began reclaiming the term — insisting that reggaeton’s DNA could not be erased, only remixed.

Globalisation and Identity

Today, reggaetón is everywhere — not as a niche but as pop itself. From Rosalía’s flamenco-trap experiments to Feid’s lo-fi reggaetón aesthetics, from Natti Natasha’s empowerment anthems to Rauw Alejandro’s futuristic grooves — the genre now appeals to multiple dialects, often to the detriment of musical quality and authenticity.

Who gets to represent reggaetón? When non-Caribbean non-black artists top the charts with a black Caribbean genre, are the genre's black and working-class origins being appropriated? In Latin America — where racism and classism remain taboo — for the white-run establishment atleast - this debate is not aired enough.

But, just like R&B, hiphop, the genre has taken its own journey in this world of global capitalism, which can't be controlled. And many of today’s artists — from Villano Antillano to Tokischa — re-politicised the sound in a way that makes sense to them, using it to challenge gender norms and reclaim space for the marginalised. Reggaeton is becoming queer, feminist, experimental — a testament to its original spirit of rebellion.

The Return Underground: Independence 2.0

Paradoxically, after conquering the world, reggaeton is returning to where it started — the underground.

Independent producers on TikTok and SoundCloud are building scenes that echo the 1990s ethos: DIY, community-driven, and unapologetically local. The difference is that now, the “underground” is digital.

New collectives and artists in Chile, Argentina, and Mexico mix dembow with hyperpop and techno. Afro-Latino communities in Colombia and the Dominican Republic are reclaiming traditional rhythms like champeta and dembow dominicano, injecting them back into the mainstream conversation. From back rooms in Bélen, Brazil or Buenos Aires, talented producers are making their own urban Latin, such BZRP - music geek turned global hit-maker, whose astonishing PR and distribution strategies engineered a reach so envious that even the original reggaetón stars want to perform on the Argentine's platform.

Meanwhile, in Puerto Rico, veterans like Tego and Ivy Queen are being rediscovered by younger fans seeking authenticity. Their early recordings — once censored — now circulate as sacred texts of resistance.

This cyclical return isn’t nostalgia. It’s evolution. Every time the system commodifies the music, new artists rebuild it from the ground up. Reggaeton, it seems, must always be reborn in the hands of those who were never supposed to own the microphone.

The Beat That Never Dies

Reggaeton’s journey mirrors the history of Latin America itself: colonised, fragmented, yet unstoppable. It is a sonic record of migration — from Jamaica to Panama, from San Juan to New York, from Medellín to Madrid. Each era adds a layer of meaning: from the struggle for recognition to the assertion of global pride.

In 2025, the genre stands at a crossroads again. It has nothing left to prove, yet everything to remember. It has conquered the world — so what does its biggest star do? Bad Bunny wanted to bring it home.

Days after releasing his sixth studio album, Debí Tirar Más Fotos - a love letter to his musical heritage blending reggaetón, bomba, plena, salsa - Bad Bunny announced that he would play over 30 shows in San Juan Puerto Rico. It became a cultural homecoming on a scale never seen before. The first nine shows were reserved exclusively for Puerto Rican residents and the stage featured a full-scale casita (traditional Puerto Rican home), a flamboyánt tree, live bomba and plena bands, and surprise appearances from pioneers like Ivy Queen, local activists, and athletes.

Generating US$300 million for Puerto Rico, the island who 30 years ago had banned the genre from the airwaves, that very genre was bringing the cheque back home. Reggaetón has come back full circle — from diaspora export back to its Caribbean source - in the most spectacular way. The greatest vengeance, they say, is success. And success it became. Because reggaetón was never just music. It was — and still is — a revolution in 4/4 time.

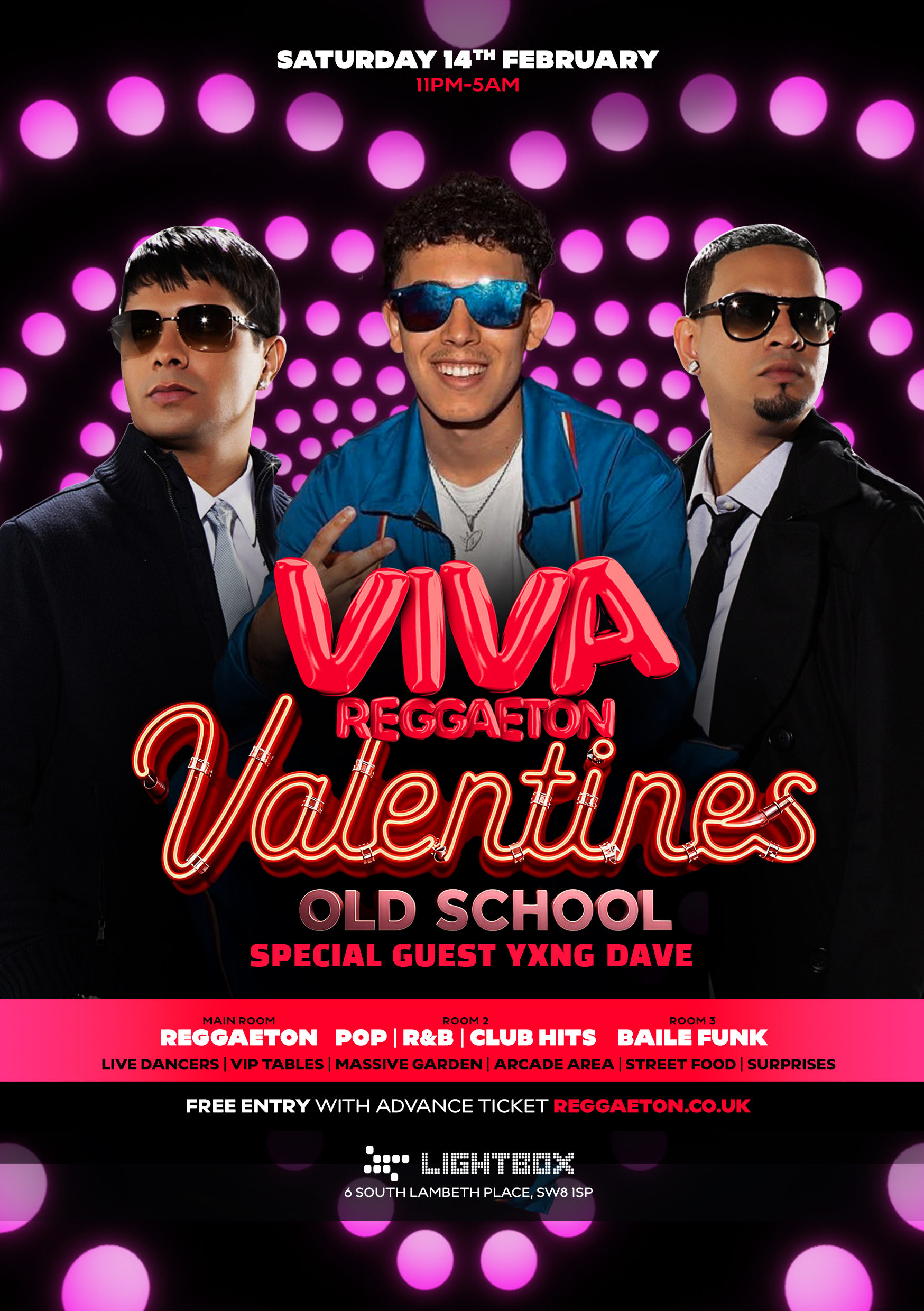

Celebrate our night of Old Skool reggaetón at Viva Reggaeton in Vauxhall this Saturday. Tickets here

LatinoLife's pick of Reggaetón's most classic Albums

Vico C: Aquel que habia muerto.

Tego Calderon: El Abayarde

Daddy yankee: Barrio Fino

Yaga y Makkie: Sonando Diferente

DJ Nelson: La Discoteca

Eddie Dee: Los 12 Discipulos

Ivy Queen: Real

Pina All star: Vol 1 and Vol 2

Varios Artist: La Conspiración Vol 1 and 2 J

Julio Voltio: Voltaje