Between 1932 and 1935, Bolivia and Paraguay were at war over an arid wilderness known as the Chaco Borealis. A small Bolivian platoon made up largely of Aymara and Quechua conscripts, led by a retired German commander, seek fruitlessly for their enemy in the arid territory.

“Here, a soldier has only two options: he walks or he dies.”

‘Chaco’ is the opera prima of writer/director, producer and lecturer Diego Mondaca (1980- Bolivia). Trained at the renowned film school in Cuba (IECTV), he started out making documentaries. The first, ‘The Chirola’ (2003) is a poetic take on the dilemmas of life and freedom for a person who has lived in confinement for a long time (prison) and then takes on a puppy as his companion. The second, Citadel (2011) deals with the apparent explosive disorder of the main male prison in La Paz, Bolivia.

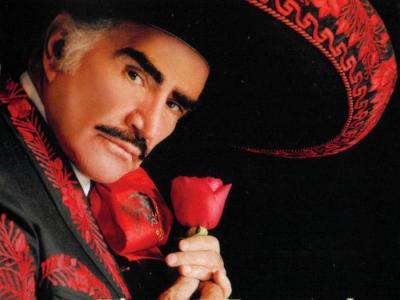

Raymundo Ramos as Cabo Liborio and Fausto Castellón as Private Jacinto

Though ‘Chaco’ is set out in the agonizing dry and sparse lands of the Chaco Borealis, this small platoon is, in effect, also imprisoned, not so much by man, but by nature itself, as the conscripts struggle to find enough water and food to survive. Aymara and Quechua people are from the high Andes of Bolivia, the Altiplano, with its crisp dry air, with their bodies designed over millennia to cope with the low oxygen levels at those heights. Finding themselves in the intense heat of the humid, low lands of the Chaco, their bodies fail them and they gradually fall ill and start to fade.

The group wander about this hostile environment, searching for their enemy in vain, only coming across the odd Wichí indians, as they erect small improvised base camps using wood, twigs, and tents. Hunger, isolation and despair gradually overwhelm them, as the futility of their quest becomes clearer to them. The enemy is nowhere to be seen or heard. They are so desperately hungry they end up killing and eating the commander’s mule, after which they find themselves having to carry all the heavy weapons and equipment. Piece by piece, it ends up lying on the path behind them. Can they survive?

It is a strong indictment on the futility of war, certainly a badly-planned one such as this. The Bolivians, with a much larger population that Paraguay probably thought they had a chance to consolidate their claim on the area, as it was suspected that it might have oil and other resources. However, Paraguay, though with a smaller population, was better equipped, with a rail network and rivers to supply their troops. The Bolivians had no such facilities and fresh supplies were few and far between, so many men ended up abandoned to the vagaries of the hostile environment. Also, the Paraguayan were hugely motivated. Their population rose to the challenge and people were even donating their wedding rings to help fund the war effort. No such zeal and determination from the Bolivian conscripts, who had never been to and would probably never have gone to the Chaco, preferring to remain in their highlands. Interestingly, both sides had German commanders.

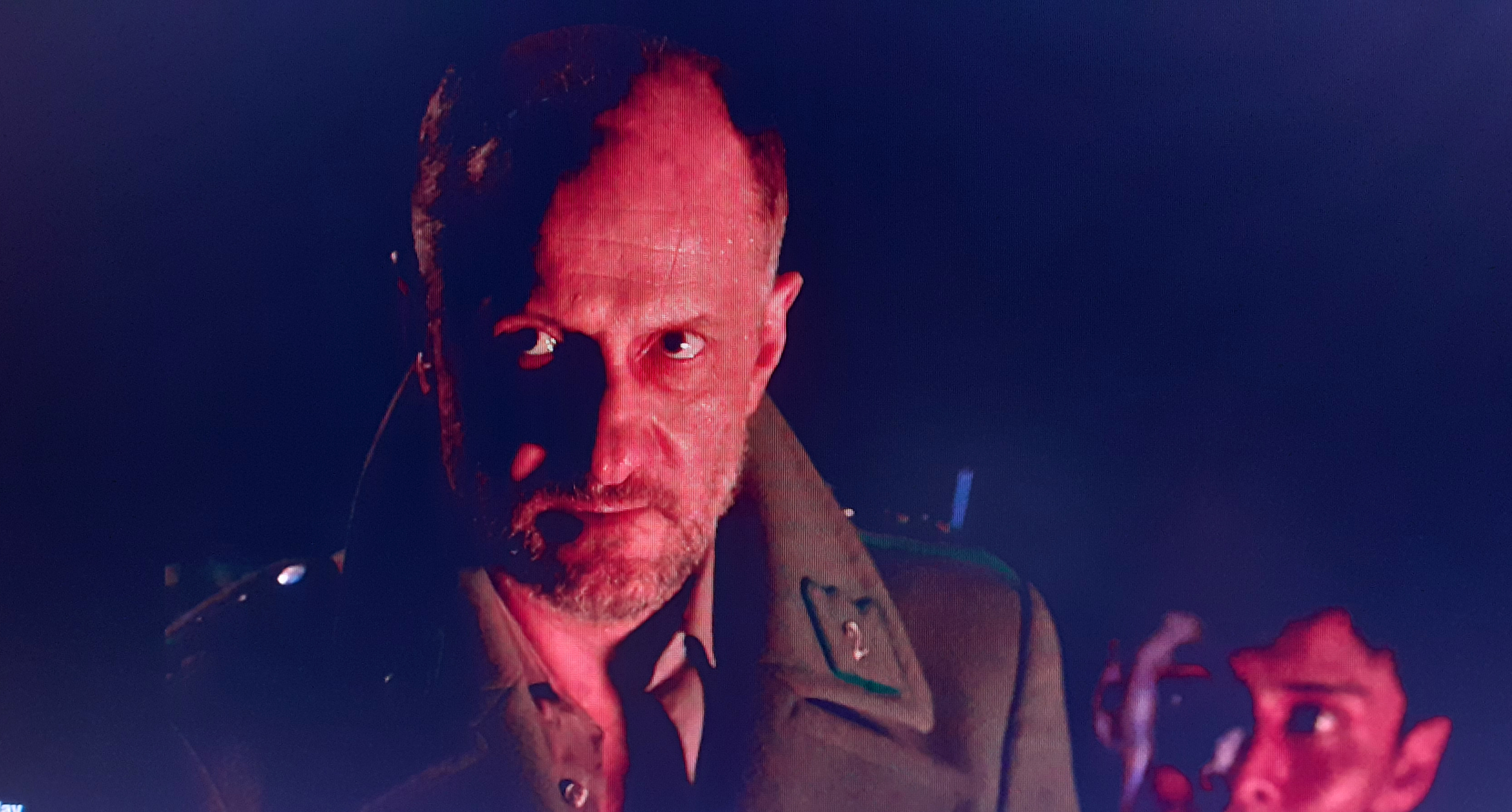

Fabián Arenillas as Capitán Alemán

Reminiscent in many ways of the dead-end isolation of Zama (2017- Lucrecia Martel), or Napoleon’s men returning, defeated, from Russia, only instead of snow and ice, the Chaco platoon have to deal with endless dust and sand.

Federico Latra’s cinematography is evocative as he takes in the parched landscape dotted with its sparse undergrowth with sweeping shots. The Chaco is, in reality, a desert and the conscripts are doomed to trek endlessly along earth trails, where all they succeed in doing is lifting clouds of fine dust that permeates everything. They collapse to rest at every chance and, at one point, they take a well-earned bath in a muddy pond.

The firelight scenes illustrate the moments when the men are able to communicate and we get to know the individuals, with their swollen cheeks of coca -leaf- chewing so distinctive of the Aymara and Quechua people. The retired German ‘Capitán Alemán’, (Fabián Arenillas) had been persuaded to lead this platoon into the hostile bush. Without his mule, his main privilege is gone, except for the while during which he continues to insist on taking a life-size female doll that accompanies him everywhere. Is it an improvised Virgin Mary?

There is a sad charm in their attempt to maintain a modicum of military order, setting up camp and putting up the Bolivian flag to the strains of very out-of-tune band with drums and trumpets blowing dust into the air.

Some soldiers succumb to their despair, hallucinate or are severely punished for trying to desert. This does nothing for the fading morale of the troops. The Aymara and Quechua conscripts that define the character of the film come up with excellent performances, in particular from Raymundo Ramos (as Cabo Liborio), Omar Calisaya (as Sub-official Ticano), and Fausto Castellón (as Private Jacinto).

Mondaca has dedicated this film to his grandfather, on whose experiences the film was inspired, and the “futility and absurdity of war,” which this film illustrates to perfection. A notable debut movie from Mondaca.

‘Chaco’ (2020) premiered at the 2020 Rotterdam Film Festival, and was chosen to represent Bolivia at the 93rd Academy Awards but was not nominated.

Cinema Mentiré organized this cycle of Bolivian films to be screened at: - The Garden Cinema –

39-41 Parker Street, London WC2B 5PQ / From January 10th – February 21st 2025.

Chaco (2020) Director Diego Mondaca

Writers: Diego Mondaca, César Díaz, and Pilar Palomero / Producers: Camila Molina Wiethüchter, Álvaro Manzano Zambrana, Bárbara Francisco, Giorgina Baisch / DOP: Federico Lastra (ADF) . Editors: Delfina Castagnino, Valeria Racioppi (SAE) César Díaz/ Art Director: Javier Cuellar Otero / Sound Design & Direct Sound: Nahuel Palenque / Music: Alberto Villalpando

Cast: German Captain: Fabián Arenillas/ Cabo Liborio: Raymundo Ramos / Private Jacinto: Fausto Castellón/ Suboficial Ticona: Omar Calisaya/ Lieutenant Rogelio: Mauricio Toledo