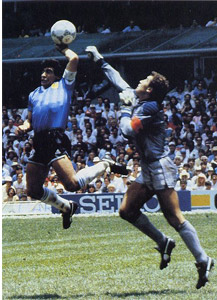

Argentina is obsessed with the dead bodies of the famous. Evita Perón’s corpse endured a 16-year secret journey across the world in a battle for possession between political forces. The hands of the bodies of Juan Peron and Che Guevara have been mysteriously sawn off. When Perón’s mutilation was discovered in 1987, labour unions organized a protest that was attended by 50,000 people. ‘There are no better examples of collective delirium than the mass convulsions of the Argentine people at the funerals of Gardel and Evita, and the return of Perón in 1973,’ says historian Juan José Sebreli. For an entire century the common goal of trying to be ‘different’ and superior to the rest of Latin America defined the nation. It was a strange breed of nationalism, a kind of collective narcissism developed into what many other Latin Americans saw as arrogance. This imaginative and highly emotional sense of patriotism is vulnerable to manipulation. Juan Perón himself, seen as the father of the modern Argentine state, was the first to take advantage of its psychological potential. At a time when immigrant society was hankering for a reference point, he rallied the nation around a simple notion: that Argentina was leading the noble battle against the economic imperialism of Britain and the US and was on its way to becoming the greatest country in the world. Perón was forced into exile by jealous militaries in 1955 but 15 years later, in the intense political atmosphere of the early 1970s, both the left and right-wing public demanded the return of their saviour. His arrival in 1973 provoked mass delirium. Perón spent his last days in power holding 70 per cent of the vote. Juan Sebreli explains Perón’s popularity as a kind of irrational attraction. He swears that even those groups – intellectuals, middle classes – who were loath to defend his totalitarian style were irrationally attracted to him. ‘A whole generation, my whole generation, is indissolubly attracted to Peronism forever.’ It was Perón as a symbol, not the force of his reforms, that was the source of his power. For the sentimental, melancholic and insecure, Peronism provided more than just the singular satisfaction of Fatherland or Mother-country. Evita and Juan offered a full Parent-nation. ‘Evita perhaps was the decisive ingredient in the personal myth of Peronism,’ remembers Sebreli. Although her sordid past was deplored by the Church and the traditional élite, for ordinary people she was a romantic heroine whose fate allowed her to take vengeance against the society that at one time humiliated her. Although the difference between the ruthless social-climbing Evita and her image as giver to the people was glaringly obvious, Sebreli claims the public invented lies to justify their own worship of her: ‘They said all the jewels she wore were stolen from rich people and would one day be donated to the public.’ The mass hysteria that Evita's funeral provoked was a demonstration of collective love for a national heroine on a scale not be seen again in the world until Princess Diana's funeral 40 years later. The Manipulation of Peronism and the Menem Years The Peronist ideal of the nation-state has been in crisis ever since – and with it the concept of nationalism which proved most convincing to the people. The brutal dictatorship of the 1970s wouldn't have been possible without Perón's implied consent when he publicly rejected of his left-wing followers on his return in 1973, a gesture which his second wife, Isabelita Perón, allowed to be maniuplated to the most sinister ends after Perón's death. Despite this betrayal of the original Peronist ideal, voters returned to Peronism only 6 years after the dictatorship ended in the form of Carlos Menem, elected on a Peronist platform in 1989. Indeed no other President, other than a Peronist, has managed to be elected since. Menem managed to manipulate the Peronist rhetoric and the old cultural symbols that inspired pride whilst introducing an ultra-neo-liberal economy that would have had Perón turning in his grave. As the once-sacred customs of late-night Tango-bar prowling, local cinema, literature workshops and cabaret disappeared into the sea of US burger joints, pop music and virtual-reality arcades during the 1990s, only a few muffled complaints could be heard of a pais vendido – a ‘country sold out’. The symbols of economic imperialism that Perón cast as the enemy were being embraced by the new rich who benefitted from Menem's privatisations. Others were too busy recovering from the scars of the dictatorship to be able to resist or point out the irony of it all being done in the name of Peronism. National Identity: From Arrogance to Insecurity Young people nowadays associate the word nationalism either with the uncontrollable left-wing ‘craze’ of the 1970s or with 'Nazionalism', the sinister militaristic fantasies which left the country in ruins during the early 1980s. ‘I’m glad we are not a nationalist country,’ says 19-year-old Estevan. ‘It would mean marching up and down school yards in military uniform and saluting the flag. Nobody believes in those things any more.’ The process of ‘opening up’ to the global economy ensured the displacement of Argentina’s traditional institutions. The Army is at its weakest point in history, the Catholic Church is losing its hold in the face of new Protestant-influenced denominations. People are resigned to the fact that Argentina never fulfilled the promises it was supposed to and you can hear them now wallowing in the other extreme "We're just a no-good country like the rest of Latin America". For a country that prided itself on being better than its neighbours, the new sensation is difficult to swallow. The immigrants who now flow into Buenos Aires bear the brunt of a new xenophobia. While the presence of US businesses is seen as something of an honour, the Chileans are resented. As one young banker whined: ‘They’ve always wanted our land, and since they can’t get that they are trying to steal our money’. The Meltdown and the Crash of National Pride Maradona - the man that moves hearts - supports Menem's election campaign The indifference and cynicism that Menem both exploited and nurtured climaxed dramatically in the financial meltdown of 2001. National pride became a shadow of its former self. Taxi-drivers and workers who once boasted Argentina’s greatness will today insist that Argentina is a pais de mierda – country of trash. Old left-wing political enthusiasts like Andres Wappner, embittered at the betrayal and catastrophic repression of los cabezitas negras - Evita's original working masses- go as far as to say: ‘This country doesn’t exist. It has borders and a flag but that’s where it ends.’ Menem coped with all this by playing to the imaginary desires of the public very much as Perón did. He pointed to the shopping mall, renovated docklands and new tourist trains and claimed that they signal Argentina’s emergence as a First-World Power. In his second election victory, he no longer relied on Peronist nostalgia. But his playboy image – playing golf or hosting Claudia Schiffer at moments of political crisis – and the flaunting of his wealth before a nation facing severe economic hardship held a perverse attraction to the masses. Like Perón, Menem was pure charisma. And just as Perón had Evita by his side to rally the people to his vision, Menem had Maradona. It is arguable how much impact the footballer’s declaration of support for Menem had during the last political campaign. But it is clear that when it comes to Maradona the famous Argentine fervour returns like a cyclone. Just as the image of Evita could not be tainted by the Church’s moralistic criticisms, when the vices of Maradona are exposed the public rally to his defence, even though the middle classes express embarrassment. It is love-hate with him, just like Argentines own self-image. The Kirchner Years - Invoking the Memory of Evita Tainted by allegations of corruption, Menem withdrew from the presidential elections of 2003, certain he would only face a humiliating defeat at the hands of the then relatively unknown Néstor Kirchner. Yes, another Peronist. In his inauguration speech, in a clear break from Menem's neo-liberalism shrouded in nationalist rhetoric, Kirchner argued for the need to go back to real equality "where the market excludes and abandons.’ Kirchner inherited a debt default that was the largest in financial history, and yet in 2005 was able to announce the cancellation of Argentina’s debt to the IMF in full, an impressive achievement. So how do things stand today? Have nearly seven years of rule by the husband and wife team of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner given Argentina back a sense of national pride? Kirchner left office in 2007 with reported approval ratings of 60%; Fernández de Kirchner won the subsequent election in the first round with 45.3% of the vote, giving her a 22% lead over her nearest rival. Yet, less then three years into her presidency, she is bruised from high-profile battles with the farmers and the media; and faces dismal approval ratings. Few amongst the Buenos Aires middle classes express anything more than a tentative support for her; almost all are openly critical. On the streets, in the cafeterias, and in the taxis of Buenos Aires, the old murmurings can be heard of Argentina, as un pais de mierda. So where did it all go so wrong for la presidenta? Fernández de Kirchner’s ascent to power in 2007 was met with inevitable comparisons with Eva Perón. She rejected the comparison, claiming that ‘Eva was a unique phenomenon in Argentine history, so I'm not foolish enough to compare myself with her.’ Yet, at the same time, she has also described herself as an ‘Evita of the hair in a bun and the clenched fist before a microphone,’ referring to the combative political style that she shares with Perón. The two women also share a certain glamour; one of the most common accusations aimed at Fernández de Kirchner is that of vanity, much has been made of her wardrobe and of the time she devotes to hair and make-up before public appearances. Cristina gives an election campaign speech to the backdrop of Evita The accusation of vanity sounds at first like a complaint from a culture that is still not entirely comfortable with the idea of a glamorous, stylish woman occupying a position of such power. One Argentine woman makes a face when I put this objection to her: ‘Perhaps there is an element of that,’ she admits. ‘But if she accompanied her glamour with concrete political achievements she wouldn’t get criticised this way. Evita was a glamorous woman as well but she actually did things. Cristina uses accusations of sexism as a shield against her critics, but she is inept.’ However, while Fernández de Kirchner’s unpopularity may not derive entirely from sexism, it does seem to have more to do with her personality than her politics. ‘Cristina comes across like your mum telling you what to do,’ says Patrick Rice, a Buenos Aires based human rights activist. Indeed she is often referred to as ‘la profesora’. Yet, in her defence, Rice points out that since the global financial crisis of 2008/09, it is not only Argentina’s economy that has suffered, but almost everywhere. ‘And Cristina has offered concrete, practical proposals to get people working,’ he says. ‘She has offered government money to local cooperatives to do public work. It is not a lot, but at least it means that they are working.’ There is one area in which the Kirchners’ record is surely to be commended. ‘On human rights it’s clear that the Kirchners are unique,’ says Rice, referring to their reversal of Menem’s policy of amnesty for the criminals of the military period of 1976-83. This was followed by the pursuit and prosecution of several high-profile figures, and forced resignation of many others. ‘Many people won’t recognise the importance of this yet,’ he admits. But surely real national pride couldn't have been restored without this historical justice that for years Argentines fought for. The Argentine Love of Gloom - an Perverse National Identity? If Perón inspired an irrational attraction, a quasi-religious feeling among Argentines, today, in the absence of a Juan Perón or an Evita, there is something else that the people seem irrationally attracted to: gloom. Many people seem given to making exaggerated claims about the lamentable state of Argentina. One girl tells me ‘things are worse now than in 2001.’ Another claims that ‘the Kirchners are as bad as the military junta.’ Pessimism is everywhere; nobody thinks that Argentina is moving in a positive direction. Rice - an Irishman who has lived in Buenos Aires for 23 years - shrugs his shoulders. ‘I don’t understand it either. Sometimes it is difficult to get people to appreciate what they have.’ After all, since 2002, urban poverty in Argentina has dropped by two-thirds; and between 2003-07 Argentina enjoyed a period of economic growth of roughly 9% for five consecutive years, a remarkable recovery given the severity of the 2001 crisis. Argentina is second only to Chile on the UN’s human development index amongst Latin American nations, ahead even of Brazil, a nation to which many Argentines compare their own disfavourably. If Argentines like to deposit their collective emotional energy into a single character, the life of Diego Maradona seems bizarrely to mirror the Argentine self-image - huge potential and talent marred by a troubled self-perception. Throughout his battles with obesity and drug addiction the public rallied to his defence. Then, following his bungling of Argentina’s World Cup qualification, and his astonishing tirade at the media – ‘suck it and carry on sucking it’ – he is also seen by many as an embarrassment. Yet, beneath the scepticism, the Argentine psyche cannot quite give up on this national icon (and their own pride), however much embarrassment he causes. ‘Make no mistake,’ says one young man. ‘If we were to win the World Cup with Maradona in charge, they would knock down the Obelisk and replace it with his statue.’ After all, it was Maradona's ‘Hand of God’ goal that helped Argentina win the 1986 World Cup and restored a piece of national pride. Just a mention of that magic moment today will put a gleaming smile on the face of any Argentine, no matter what class. It doesn’t take much imagination to wonder what will happen to that hand once he is dead and gone.