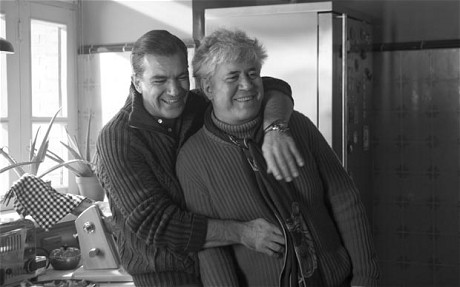

For almost 40 years Pedro Almodóvar has been making films that have shaped understandings of what constitutes Spanish cinema. His daring narratives, his willingness to play with genre, his merging of the tragic and the comic, his attention to mise en scène and décor have made him one of the world’s great auteurs.

Nobody makes films quite like Almodóvar. His films manage to move from the political to the personal and comment on the society in which he lives and works without ever appearing dogmatic. Attention has been paid to his bold exploration of sexuality and desire, his use of colour coding and meticulous style, his use of music and intricate plots, but I would argue that the extraordinary performances that ground his work are fundamental to any understanding of the Almodóvar brand.

Almodóvar understands acting and actors. He never went to film school but rather learned his craft 'on the go'. His early work dispensed with continuity and conventional modes of framing but the idea of performance was always a central consideration in his narratives. He emerged in many ways from the theatre, performing in the 1970s with the experimental company Los Goliardos where he met Carmen Maura. It is perhaps not all that surprising that one of Spain’s leading theatre directors, Lluís Pasqual, who appears rehearsing Marisa Paredes at the end of Todo sobre mi madre/All About My Mother (1999), has commented that Almodóvar’s influence is discernable not just in Spanish cinema but also on the Spanish stage:

“He has had a huge impact on Spanish audiences in terms of dealing with matters that seemed to be taboo, were viewed as indecent, or appeared to be subjects for a literary minority rather than for broader theatre or film audiences; he has had a huge influence in that sense.”

Similarly in the way in which he works with actors, Pasqual argues that Almodóvar “seeks a truth — as is often the case in the world of performance — but not a conventional or comfortable truth — the truth never is — but a truth within a madness that is part of the existence of contemporary humanity. This is evident in the characters that he puts on the screen. They employ a specific language and travel from life to the cinema and from cinema to life, just as is the case with certain emotions that are no longer marginalised and have been adopted in everyday life.”

Indeed, few directors are able to elicit the performances that Almodóvar secures from actors as diverse as Chus Lampreave and Blanca Portillo. And while there have been male stars, as with Antonio Banderas and more recently Gael García Bernal and Lluís Homar, it’s the women who usually steal the show. There have been a range of chicas Almodóvar over the years but in all cases, it’s possible to make a case that each has produced their finest screen work with this Manchegan director.

Almodóvar has placed women’s issues centre stage. Taking inspiration from Hollywood’s woman’s picture he has dramatised family squabbles and conflicts, re-fashioned feminist discourses, dramatised grief and solace, and sought, in the words of one of his earliest heroines, Luci, to give women the space “to find their true selves”.

In the process he has offered world cinema a number of its most beguiling and enchanting women characters. From the reformed killer Sister Estiércol “Sister Manure” played by Marisa Paredes in Dark Habits to Chus Lampreave’s quirky grandmother in ¿Que he hecho yo para hacer esto?/What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984), Penélope Cruz’s luminous Sister Rosa in Todo sobre mi madre/All About My Mother (1999), and Elena Amaya’s resourceful Vera Cruz in La piel que habito/The Skin I Live In (2011), Almodóvar has presented women as creative beings who have the capacity to ingeniously transform their own lives.

And it is this focus on transformation and alteration, renovation and change that has defined so much of his work. The process of creating a role, theatricality and role play are the very DNA of Almadovar’s cinema. Is it any coincidence that so many of his characters are performers? Acting is part of their way of life. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that his films have drawn on a wide range of performance registers from the high theatrics of the early work to the more contained acting style of the work that followed Carne Tremula/Live Flesh in 1997.

Almadóvar’s work with actors often involves three months of rehearsals prior to shooting and the crafting of a character using external tools (wigs, costume, prosthetics, make-up) as well as discourses more associated with the internal processes of Method acting. The programme of five films presented in this season looks at the performances he has constructed with actors – from the melodramatic register of La flor de mi secreto/The Flower of My Secret (1995) to the high theatrics of All About My Mother and the noirish drama of Los abrazos rotos/Broken Embraces (2009).

The season also brings to London three actors to discuss working with Almodóvar on creating a role. Lluís Homar, the smooth-talking blackmailing Berenguer in La mala educación/Bad Education (2004) and the blinded grieving screenwriter Harry Caine in Broken Embraces; regular collaborator Marisa Paredes whose desperate writer Leo in The Flower of my Secret functions as a veritable contrast to the ominous housekeeper she embodies in The Skin I Live In; and Antonia San Juan, the captivating, resourceful Agrado in All About My Mother.

Interestingly, all three are performers who have forged trajectories in theatre – and it’s worth noting that Almodóvar has spoken of the fact that he often casts productions after seeing the actors work on stage. Carmen Machi, for example, is the sole protagonist of La concejala antropofaga/The Cannibalistic Council Woman (2009), a short film that harks back to Almodóvar’s early super 8 films: the monologue is a spin-off from Broken Embraces created especially for the mischievous Machi.

Almodóvar’s style may have changed – from the in-yer-face eccentricity of Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980), his first feature, to the melding of horror, melodrama, noirish thriller, and sci-fi that marked The Skin I Live in – but the focus on play and artifice has remained a constant. “Acting Almodóvar” offers a few clues as to how key roles have been created and what it means to work with one of the world’s greatest living filmmakers.