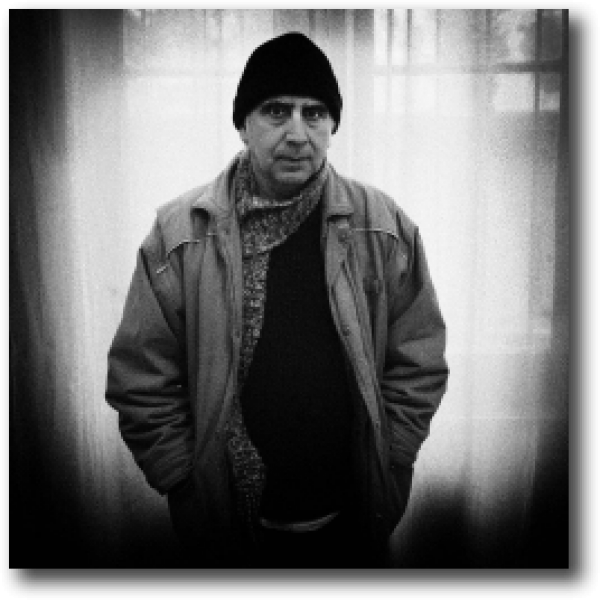

Mauricio Valenzuela’s passion was to be a painter. He had been familiar with photography since he was a child, but he wanted to work in, what he complains, the Academy describes as a minor art: Watercolour. Even today, he insists he still thinks with a pencil. He had a very disrupted school life as, due to his consistently bad behaviour, he was expelled and shunted around no less than 13 school before he ended up, aged 16 in a special college, run by monks

“At that time, I wanted to repair electric guitars, Imagine! I can’t even play! But a group of my friends played and sang like the Beatles, so I represented them. I can’t sing or dance but I loved parties and we played in colleges.”

The guitar repair course turned out to be full so Valenzuela ended up joining a Painting Course run by two renowned painters, Humberto Pérez and Beatríz Cortés, who came from the Academy of Fine Art. This is where Valenzuela learnt to prepare a series and structure a project. Through them, he met visiting artists from abroad and the USA and participated in the many discussions on the Arts and Politics. From then on, he resolved to become a visual artist himself.

Supporting Allende during his presidency was the Unidad Popular (Popular Unity). It was comprised of most of the Chilean left, including the Socialist, Communist, Radical and the Social Democrat Parties, the Independent Popular Action and MAPU. By 1971, even the Christian Left had joined them and by 1972 the MAPU Obrero Campesino as well. The UP (Unidad Popular) wanted to promote a peaceful transition to socialism. This involved the nationalization of some industries, and significant agrarian reforms, but what really changed Valenzuela’s life was the social assistance they gave to communities, including artistic collectives.

“I could go to a commission where I would be given food daily and they would pay for my studio, so what for some people, was a demonic time, [that period of the Popular Unity], was paradise for me!”

Nevertheless, it was a wrench for Valenzuela to move from painting to Photography.

“It’s as if you are madly in love with a woman but she says, ‘No, I do not love you’… and then you’re walking around the street disillusioned and another one is following you saying: “I love you, please love me too”, and then you’re the one who says: “No”. So, although painting defined me and I am [still] in love with painting. I have had to admit that Painting does not love me! As a painter, I would get obsessive with the object of my attention. I like very realistic painting, so I was obsessed with what it ‘really’ was intrinsically, its place and its ‘being’ in reality. But with a camera in-between me and the object, I realized there was a space to reflect. When I first started to take pictures, I was totally spontaneous, probably because initially I didn’t care if it was a documental image or not, I just pressed the button freely. It was instinctive.”

But what nobody can be taught emerged, and Valenzuela discovered he had an eye and a sense of timing essential to photography. His images finally garnered a proper reception from his artistic friends, who had been as kind as possible about his realistic watercolours, ‘umming and ‘arring avoiding having to give an opinion. ‘

But once Valenzuela had been invited to join the Photographers Association (AFI) and gathered some images for his first exhibition, he realized he had finally found his mètier. It was encouraged by his artistic friends, in particular before the coup. The period of the Popular Unity was very rich in cultural activity, as intellectuals from all over the world poured into Chile: -

“We were presenting theatrical productions of Berthold Brecht and Depanico Theare and organizing lectures. It was a kind of independent Marxist community … between 1970 and 1973. I sometimes slept in the streets and even took acid. The ideological battle was so violent that the feeling of freedom was explosive, I have never been able to live like that again. It was so easy to live independently at that time.”

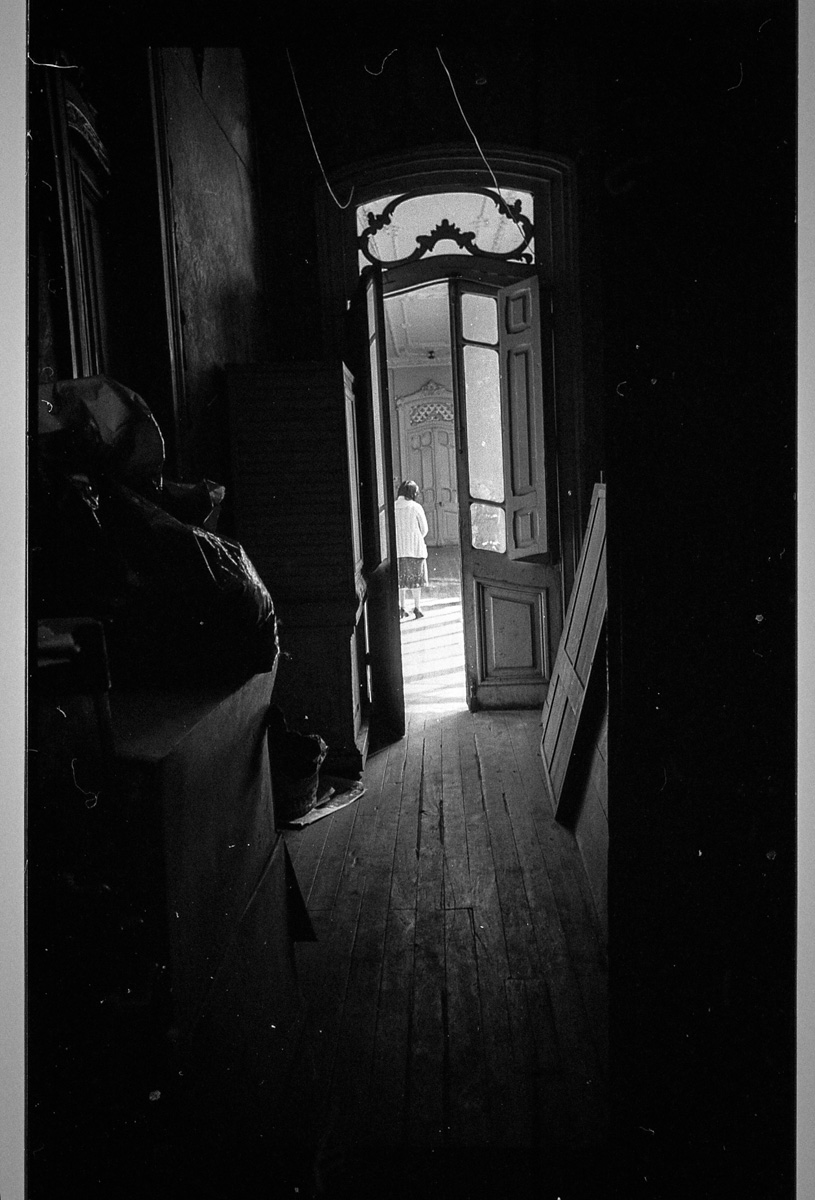

Valenzuela and his artistic friends, including some anarchists, lived and worked in an abandoned house that functioned as a cultural centre. Groups would emerge and paint murals. They had a school where left- wing teachers would come and teach people how to read and think, not just about politics.

When the coup took place, it was devastating for them all. The place was raided and Valenzuela felt his life had ended. The lack of work and the emotional turmoil turned him to booze and began to live almost like a homeless person doing odd jobs sign painting lorries and shop fronts.

He was rescued by Teresa, a painter and pedagogue, who was to become his life partner and bear his children. She had a studio in a room at the Palacio Larraín. The Larraín family had built this remarkable art nouveau palace in 1913 and occupied it until 1965. Valenzuela and Teresa then rented a massive room in the palace, where they lived surrounded by stunning architecture, yet in almost abject poverty, as they had to share the bathroom and kitchen with other tenants. Valenzuela then created a studio in the tack room above the stables at the rear of the palace where, encouraged by Teresa, he restarted his photography.

In the early days, photographic equipment was very expensive, being mainly imported from Germany and Switzerland. During Allende’s presidency, cameras from the Soviet Union began to be imported. These were heavy but sturdier copies of German cameras. One of the most popular was the 35mm SLR Zenit, being an exact copy of the 1932 Leica ii: -

“They looked very professional and expensive but they were actually really cheap. I started on one. There is a legend that because one of Pinochet’s Generals was a photography enthusiast they continued to import these ‘sacrilegious ‘Russian cameras even after the coup and flooded the market, but it did mean that everyone could afford a camera!”

Working during the dictatorship was a difficult task: -

“If I had my camera, I would be detained in the street. It was almost impossible to take photos at that time, that’s why in my images, the people are small, [photographed from a distance]. It was also hard, because if the people you were photographing thought you were with the Regime, they assumed you were an undercover agent, and if they thought you were a socialist then they assumed you were targeting them for goodness—knows – what.”

It was an ironical situation as Valenzuela liked to photograph in run-down areas of the city and there were times when he was ‘rescued’ by the police who thought he was the one in danger of being assaulted. Valenzuela had a wealthy uncle who despite being a bank manager, was also a well- known photographer, [Miguel Font] and he was instrumental in encouraging Valenzuela to join the AFI, the photographers Association, and exhibit his work. He bought him a Nikon with a telephoto lens: -

“It was as if today he had given me the latest Mac model with a printer”.

As Valenzuela explains, the Pinochet Military Regime stood down in 1989 with extended negotiations. These exempted the army from any reprisals. This has meant that there has never been a process of healing, a process of Truth & Reconciliation, such as those that took place in South African and Argentina. People have not had the chance to be heard, and no one has been brought to justice. Valenzuela believes there is a conspiracy of silence: -

“Today, I believe there is an attempt to impose a new ideological memory, because there are people that they want to prioritize… they obfuscate concrete and indisputable facts, that people were thrown alive into the sea, that people were beheaded, burnt alive, even some people abroad were murdered… these are concrete facts. But there are sectors that want to create a curtain of mist to protect people who, in some cases, for reasons of greed or egoism, remain in power… There is a collusion to forget… so, I believe that Chile continues to limp on with an open wound…”

Life for Valenzuela at the moment is full of contradictory emotions. His wife is sadly ailing with Alzheimer’s disease, and after five long years of caring for her, he has had to accept that she be placed in a home. At the same time, the world has been finally opened up to him at last as an artist, an unthinkable situation only two years before.

Chantal Fabres, (of CF ART) who specializes in Latin American Art has organized shows in Europe, starting in London where he shares the exhibition with Chilean Mario Fonseca at Austin/Desmon Fine Art. He will then continue on to Sweden to participate in the ‘Landskrona Photo Festival 2018’, thanks to Christian Caujolle.

Meanwhile Mauricio Valenzuela continues to work in his field: -

“Most of my photographs are about our journey through life. I take pictures of what I call “the street”, because that’s where life is to be found. You can establish certain thought structures but if they’re not linked to the street, life and reality, then they’re worthless.”