My mother was never a grown up, in the way others’ parents were. When she picked me up from school, she would wear an Afghan coat, matching shaggy perm and platforms. She would smack on heavy black eyeliner as she waited, looking into the driver’s mirror of the bashed up brown station wagon.

But now she looks respectable. She could be a businesswoman in her trouser suit. This new respectability is not because she is over 60. Before, she would not conform because she did not share the values of those who did. Now, she is prepared to conform because she is pitting herself against the state in which she lives.

My mother lives and works in Colombia, a country where left-wing guerrilla groups and right-wing paramilitaries kidnap and kill in their battle for land and power. She has left her large Victorian house in Crouch End and her successful translation business to put her life on the line, to live communally, work in disease-ridden places and court hostility which could become deadly.

Her job with Peace Brigades International (PBI) is to accompany some of Colombia’s most threatened people: representatives of human rights organizations who are targets for the paramilitary groups. Her visits to embassies, government ministries and military establishments drives home PBI’s presence and, along with an international network of influential people that PBI alerts should anything happen, provides the deterrent for the paramilitaries who want to eliminate their protectees.

In the taxi from the airport mum is bursting to tell me about the people she has been assigned to accompany: a lawyer called Alirio Uribe Muñoz, President of Colombia’s most important Human Rights Lawyers Cooperative, which investigates the collusion between army generals and paramilitaries in massacres, the Popular Women’s Organization, who through soup kitchens and workshops, teach non-violent conflict resolution to children and Justicia y Paz (literally Justice and Peace) a Jesuit-founded group who help run peace communities in the regions. The price of their denunciations and demands for justice has been assassinations, torture and constant death threats.

“I find it incredible that anyone wants to work in human rights here when they see what happens to them,” she says, admiringly.

“But you are working for human rights here,” I point out.

“Oh well, you know me…. I never think that anything will happen to me,” she replies flippantly.

We arrive at a big house in a decent but not posh neighbourhood, which she shares with 12 other Brigadistas (most of them Europeans, some Canadians and Americans, all half her age). She has a mattress on the floor, a small stipend for essential needs. She is less tolerant of indulgence. Besides, she doesn’t have much time: she is up at the crack of dawn, puts on her little logoed jacket, arranges her blonde hair and goes to fetch her protectee. She is up till late writing reports.

My mother is over the PBI age limit for new recruits. “Most people her age can’t adapt to the lifestyle: the chaotic and crowded Bogotá house, the discomforts in the fields, they are too stuck in their ways,” says the youthful Catalán team leader Jumón. But Ann, he says, has the “fighter spirit.”

She has always had that get-on-with-it attitude to life, something to do with her post-war Mancunian roots I reckon. She began work at 18 without a university education - anaupair, an airhostess, a secretary - but she picked up languages like they were second skin. She married my Dad, a Reuters journalist, and went with him to Argentina, where she had my brother and I. On returning to England, she got herself a degree in Latin American Studies and set up her own small subtitling and translating business. Despite her success, she always had a strong social conscience. I remember our house being full of refugees from Latin American dictatorships and being dragged to protests against US support for them. Her solidarity was more out of an instinctive disgust of injustice, a soft spot for the underdog.

The months before my mother’s decision to take off, she sat in front of the telly watching the war in Afghanistan and then Iraq. She got very depressed. Such hypocrisy, she said, such deceit and media manipulation. “People’s lives, let alone the underlying causes of conflict, don’t seem to count at all in all this geo-politicking and military bravado.”

She felt impotent. And then, suddenly, she announced that the only way to keep up her morale was to take action. She had learnt about PBI when she was translating the book of Nobel Peace Prize winner Rigoberta Menchú and saw they were working in Colombia. She no longer had a husband to look after, her children were gown up, she was finally free of responsibilities. It was time to do her bit for a better world.

Can you make a difference?

In her cupboard-sized room, mum tells me I have arrived at a bad moment. Days before, the Chief of General Staff, General Mora Rangel, had called a press conference, in which he accused the peace communities of harbouring terrorists, and Justicia y Paz, who accompany them, of belonging to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). News footage claimed that the fence erected by the community to keep armed actors out, to be a demonstration of the 'concentration camp' where Justicia y Paz trained guerrillas.

The next day Mum heads for the British Embassy for a meeting with British aid agencies and a delegation of visiting MPs. She tells one of the MPs about the threat against Justicia y Paz and the community it accompanies. “We have been accompanying Justicia y Paz for ten years. It does very important work protecting the forgotten people here in Colombia. It´s important we support them now. ”

President Uribe makes a speech – it is broadcast on the second day of my visit – saying that terrorists are “hiding behind the flag of human rights groups”, that “lawyers cooperatives” are “spokespeople for terrorism”. In saying so, he lowered the political cost of attacking the people PBI accompanies and made it easier for the state to move against them; his accusations, left dangerously at the mercy of paramilitary (and military) interpretation.

The US and Britain have rewarded Uribe for his counter-terrorist efforts with political and military aid. They praise the dramatic decline in massacres over the last year. And yet the number of cases of arbitrary arrest coming in every day to the Lawyers Collective from the regions is overwhelming: 150 people in Urabá, 20 in Barranca, 38 in Arauca, 35 in Cauca, not through arrests warrants but via hooded informants pointing at people. Disappearances, in the old Argentine and Chilean sense of the word, have also, curiously, shot up.

In the PBI house, my mother and her team are receiving a sudden spurt of new petitions for accompaniment. PBI has to tell one women’s organization, whose leader has had her 16 year old daughter raped and murdered and her son abducted with the promise that other children and then parents will follow if she doesn’t stop denouncing, that it just doesn’t have the resources to offer her.

“It reminds me so much of the year we left Argentina,” mum says, shuddering. There, in 1976, young boys shouted their names and ID numbers out of windows as they were being carried off in unmarked cars to join what would amount to 30,000 other “disappeared”. She remembers how the Argentine government also accused human rights groups of insurgency. Having to meet the Justicia y Paz leaders in bars because they are afraid to go to their office, brings it all back.

“But do you really think you can make a difference?” I ask

“I think if our accompaniment allows the likes of Alirio to do his work, by being an obstacle for those who want to bump him off then that is helping. The cases Alirio investigates may not be heard now. But everything is recorded and that means that in the future people will know what happened here, and who were the military and government officials responsible for it. When they enter a restaurant people will stand up and leave and one day, however far away, they will be brought to trial like it is now finally being done in Argentina.”

Heading for the Jungle

The following week mum is sent to accompany a bus going to the peace communities in the province of Chocó. The peace communities were set up after massacres and displacements at the hands of paramilitaries. Father Javier Giraldo, founder of Justicia y Paz (and most other Colombia NGOs), was instrumental in the process. He began by collecting testimonies from survivors of massacres such as the one in Mapiripán in 1997 where paramiliaries tortured fifty campesinos for six days before killing them, quartering them and throwing them into the river. In years of massacres like these with proven complicity of the armed forces, almost no one has been punished. But, to protect themselves, these rebuilt communities refuse to give support or information to any armed group, refuse to provide “paid informants” or “peasant soldiers” to the military or allow guns in their villages.

Ten years on, only two remain in Antioquia and Chocó: San José de Apartado and CAVIDA (standing for Communities of self sufficiency, Life and Diginity), subject of the “concentration camp” controversy. Others started by Justicia y Paz in Antioquia were unable to resist the pressure exerted by paramilitaries and the military while Uribe, then governor of Antioquia, tried out his civilian-military cooperation programme, now national policy. The price of survival for San José has so far been 120 assassinations over the last seven years.

Now PBI, at Father Javier’s request, watches over both of them from the nearby town of Turbo, where the Brigadistas are stationed and, in twos, take turns in staying with the communities.

Father Javier also has an arrest warrant being issued in the paramilitary-controlled town of Turbo. “My personal strategy is not to recognize the legitimacy of the judicial process.” He says. “To refuse to talk, to refuse the lawyers they provide and if possible to refuse to be captured at all. I know this sounds a little heroic but, when the justice system has failed on almost every count to punish the military officers involved in massacres, failed to enforce protective measures for us as human rights agencies have told it to, how can we trust it?”

We leave San José for CAVIDA. Father Javier heads the other way, this frail, shy and serious old man, an award winner for his fight for justice, on the run from the law.

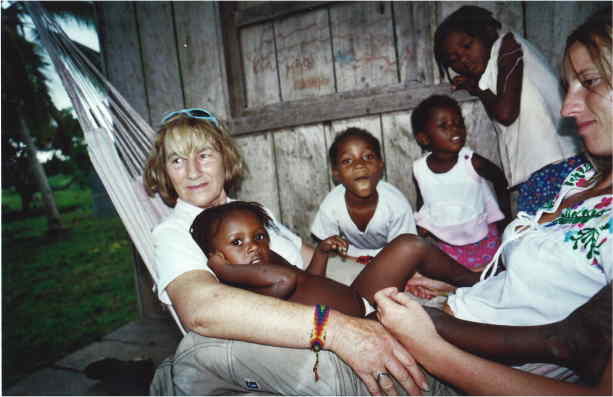

From Turbo we take the PBI speed boast across the Gulf of Urabá and then are carried up the Cacarica river in a dug-out canoe. Monkeys shriek from the trees and huge rainbow butterflies flitter in our faces. CAVIDA is a messy array of wooden shacks on stilts in the middle of the jungle, each with a big container to collect rain water in the absence of running water. There is mud everywhere, and we have to go to the toilet in the bog outside the fence (the famous “concentration camp” one), carrying a machete in case the snakes bites us.

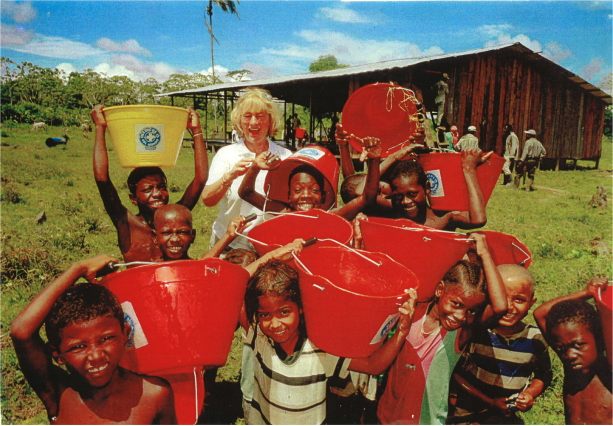

Mum doesn’t seem fazed by the discomfort. She says that she has always liked simple things. She swings on her hammock on the porch of PBI’s hut, sitting right next to Justicia y Paz’s, and watches children with the muscles of workmen carry buckets of water, paint walls, bang nails. Even in work they are ways laughing, singing and dancing. With no electricity, TV or Playstation, everything they do they turn into a form of entertainment, even the candlelit services given by visiting priests in the palm-roofed round house. After the hymns and prayers, the drums keep going, the congregation keeps singing, grandmothers dance with toddlers, husbands with wives, and laughter and rythmn can be heard long into the night.

The community is particularly crowded at the moment, CAVIDA was originally in two parts, Nueva Vida (New Life) and Esperanza en Dios (Hope in God), but since May, the army has been camped outside the gates of Esperanza. “The Cobra has arrived and is ready to raze” sang the soldiers of the 17thBrigade’s Cobra division. They burnt their rice and corn fields, and ordered all the traders in the nearby town Turbo neither to buy from nor sell products to the residents. While strangling their economy they tempted the boys to be informants with wads of cash and tried to bribe the girls to become their girlfriends. As a result, Esperanza had to join Nueva Vida, leaving their land..

“If only these people could just be left alone,” Mum says, observing from her hammock. “They could have a really nice life.”

Until 1997, these people lived untroubled by the conflict. Then one day in February at 3 am, paramilitaries and members of the 17th Brigade marched into the village, rounded up the community and told them they were looking for terrorists. They ordered one of the young men to climb up a coconut tree. When he came down they slashed his hands off. As he ran around screaming, they caught him and cut his head off. Laughing, one of the soldiers picked the head up and began to kick it to his mates, who proceeded to play a game of football with it.

Later that morning 3,000 campesinos drifted into town and local police herded them into the sports hall. After several months, encouraged by Justicia y Paz, the community began to denounce the 17th brigade to the government and demand their land back. It took three years, squashed like sardines in a hall before the community was granted the return of 103,000 acres of land. It even won a complaint against the local timber company for its illegal deforestation of their land. The government promised to provide CAVIDA with civilian protection, rather than military and the paramilitaries of Turbo had to accept a temporary defeat: “Let the monkeys return, we’ll get you later” they mocked.

One wonders why this community poses such a threat to the paramilitaries and the military and why the state refuses to give them the civilian protection they ask for.

“It’s clearly not just about fighting the guerrillas. The paramilitaries have their own agenda…. they want the land,” says Robert Goldman, of the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. Chocó’s beauty betrays it’s rich timber and palm oil resources, and its location, connecting Colombia to Central America, has sparked the interest of “mega-projects” – gas pipelines and fibre optic cabling. Goldman says these economic interests are at the root of the problem. “I have a sense the paramilitaries are in league with the timber people. There is no doubt that they want Justice and Peace and PBI out of CAVIDA. They inhibit what they want to do.”

The military also has its agenda. Weeks before General Mora Rangel made the accusations against Justicia y Paz and CAVIDA’s leaders, the constitutional court reversed a decision and finally enabled the communities to participate in the case against the 17th Brigade.

But there is a wider political reason. Peace communities have no place in the militarised society that forms part of Uribe’s Democratic Security solution. If they succeed other might want to follow.

“They want to drag us into the war with informants networks that tear apart our social fabric and weaken us, so that we cannot be strong as a community, and demand our rights,”said one of CAVIDA leaders being accused of terrorism. “They want the paramilitaries to control us and make us live in fear so we are scared to question anything the government or big businesses does. They want us to live like they live in Turbo, work on the plantations and stay shut up.”

Indeed, in CAVIDA, for all their trauma, the kids are open and affectionate. They are informed about their past and the rights they must defend. The girls talk about their female dignity that they will never pawn, and boys write vallenato songs about their community and it’s plight. In paramilitary controlled Turbo, billboards advertise Uribe’s idyllic Colombia of children playing and soldiers running Rambo style through the jungle, but where nobody will talk. A culture of silence prevails.

After months of delay, the Director of the government´s Human Rights Programme, Carlos Franco, finally flies in listen to the community, babies, pigs and all, under the palm roof. He sweats and yawns incessantly while the community articulates its strife, in the best if long-winded way it can, before finally telling it he can do nothing more than be their broker in a deal with the 17th Brigade. “You must talk with the army, everyone in the rest of the country does.” He demands with a why-should-you-think-yourselves–so-unique impatience. “They are your security.”

“With all due respect, Minister,” they answer, “The 17th Brigade is the cause of our insecurity.”

For Father Javier, Uribe’s military solution is a paramilitary solution, institutionalised like never before by this government, and supported by a desperate public in much the same way as many Argentines supported the coup in 1976, to the country’s peril. The alternative view of those that PBI protect is that Colombia will never live in peace until all the parties address the underlying causes of the conflict, namely injustice and poverty. And this, I realize, is at the root of why my mother is here.

“The one thing I have become more convinced of over the years is the need to support people who want to create spaces for peace and justice,” she says. “I don’t want to sit back and accept a militarised world, which arms of the population. It is the end of civil society.”

I find it exhausting observing the observer. But this is my mother’s new life and I wonder if she will ever be able to live normally again, amidst the frivolity and lifestyle indulgence of trendy Crouch End. Even as we sleep under our mosquito nets, she is convinced she can hear the distant zumming of illegal tree fellers. In the morning, her conviction is confirmed, as is the fact that two Justice and Peace leaders have had to leave the country. That means two less to protect the community – a small victory for its opponents. When will her hope run out I wonder?

But it is not so easy to give up, as I discovered when my mother joked flippantly that the Brigadistas were kind of useless really. Betty, an accompanee, nearly cried “Oh Ann don’t say that please! I look to you to make a bit of sense of what I am doing, because sometimes one gets lost: We are born in violence, we grow up in violence, I am bringing my children up in violence. The only thing I have, to differentiate myself from this is this struggle to find a different tool against their guns. If it wasn’t for you I wouldn’t be here with this glass of wine talking about these things. You give us this space.”

My mother is due back home next year, but I imagine she will stay. Her jokes about how useless she is (still that Mancunian self-deprecation) hide a commitment greater than herself. As do her complaints about young people telling her how their parents would never dare to do what she is doing: “What does that say? That says more about their parents than it does about me. There are lots of people doing extraordinary things in the world, much more extraordinary than me. Just look at the people around me.”

For more information in Peace Brigades International go to:http://www.peacebrigades.org

To find out about Ann Wright's accompaniment work in other parts of the world go to: www.palestinejournals.co.uk